Jump to a section

Burnout is a husk-maker

Time.

All I’m ever asking for is time.

I just needed time to clear my mind.

Until a little over a week ago, the story I kept telling myself was that there was no time for anything.

Capacity planning, road maps, individual goal-setting, holding the engineering bar, being the subject-matter expert for my particular area of the app (which is touched by every other area of the app), writing documentation for process, writing documentation for project progress, writing documentation for individual progress of team members, launching features, soothing stakeholders, fielding bugs, coordinating with other teams, meetings, meetings, meetings, aah!1

The thing is, that list is (mostly) comprised of general requirements for the job that I want and am good at (engineering manager). So why the chaos? If these are the things that are expected, why did I always feel like I never had time to do them?

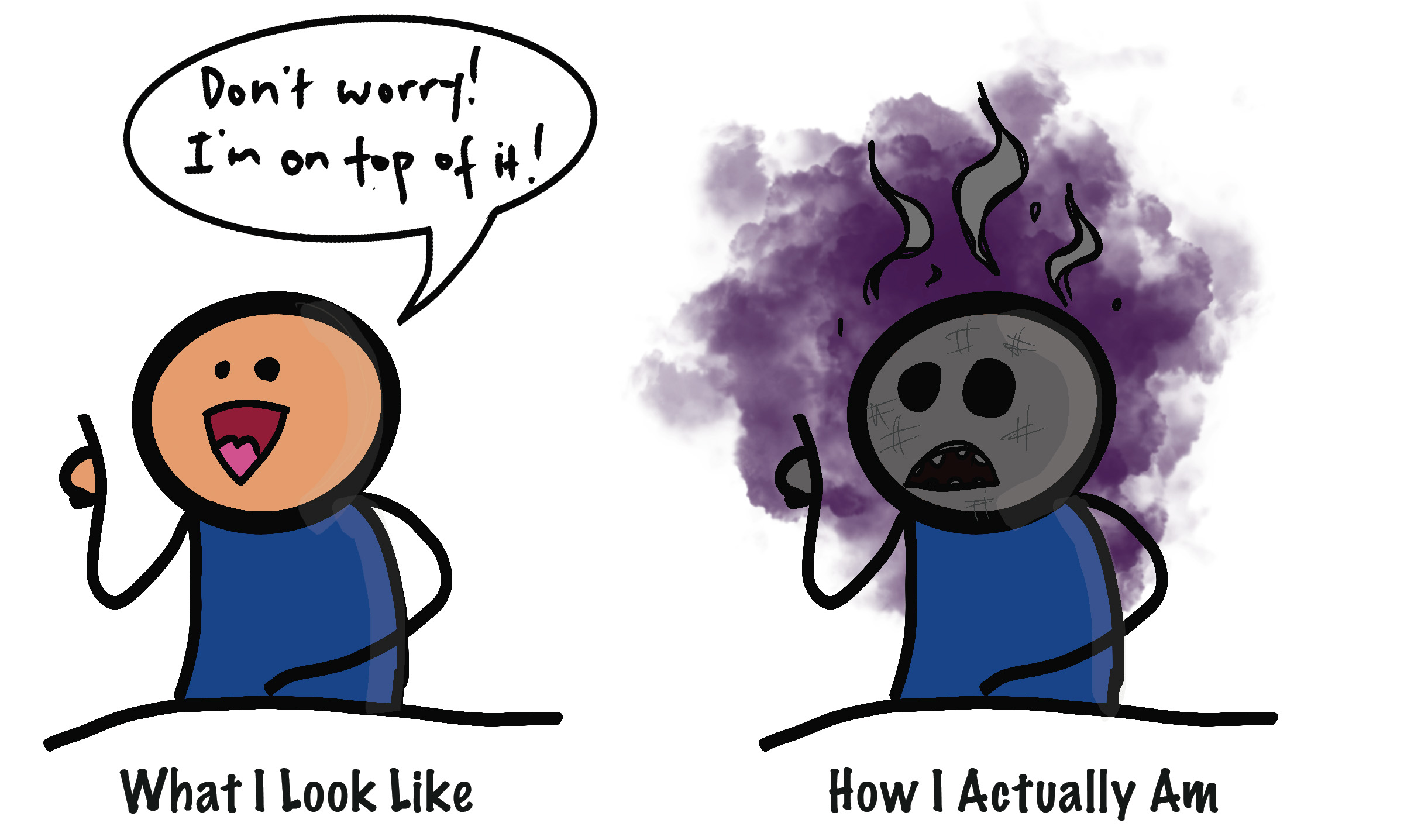

This, unfortunately, is a problem that I’d seen before in myself and others. As an engineer, I also found myself buried in work, still delivering but feeling like I was never fully on top of everything. The people around me were gracious and appreciative (most of the time), but my to-do lists were long, my brain was full, and there was this feeling of letting everyone down.

Hello, burnout, my old friend.

(hop down to the things anxious engineers do that lead them to burnout)

Burnout happens to everyone. Self-reported statistics by polling engineers in 2021 – the height of the go-go-go pandemic era in tech – and 2023 put the number of people suffering burnout in their career at between 73% and 84% (1 , 2 ). But, anecdotally, I’ve seen the anxious person who is also an engineer suffer from burnout the quickest and the most deeply. And I am an anxious engineer.

I’m not going to spend a lot of time talking about burnout in general since so many people talk about it (everyone is struggling and struggles get the clicks). I’ll direct you to google.com and maybe just a few of my favorites (1 , 2 , 3 ).

What interests me more is the anxious engineer and how we struggle mightily. Why is that? Being able to hyper-parallelize thoughts and leverage nervous energy should be a boon to the engineer, right? I kid, since those are the running-wild aspects of the anxious brain that get it into the most trouble. But why is that?

It doesn’t matter if you’re at a startup, a mid-level engineering practice, or a MMAAN2, there’s a lot happening at once. The higher you are in the organization, the more you know about and the more that is rolling around in your brain. If you don’t have good engineering habits, you face being overwhelmed. And I slipped on my good habits. The worst part about burning out is missing all the red flags as you sink deeper into it.

Allow me to walk you through my many pitfalls and how I was “surviving” while ultimately making myself miserable as a cautionary tale of how to not let your anxiety boss you around.

You’re in denial about being swamped

“Denial? It’s all the stuff I have to do! It’s why I’m here!” But how I got here is more the question. As I drowned in the boggy waters of requests, tasks, and ambition, the things being done popped to the surface in tiny bubbles. But was that because of a flash flood of things needing to be done at once (as I insisted) or a slow rise of things compounding on each other?

The feeling of being overwhelmed by tasks that are not overwhelming by my standards is a weird thing to explain. Imagine an essay. The feeling I have when starting to write anything is that the whole of what I’m about to write comes to me condensed in a small payload, hits my brain, and then explodes everywhere. The wave of words is too much to handle, so I have to let it subside before taking action. And we begin a procrastination phase.

This happened to me while writing this section. The whole of what I wanted to say knocked me over with such force that I reflexively reached for the safety of my phone and checked Instagram. There’s nothing on Instagram that I care about or need in this momen3. It’s the same reason people may passively binge rewatch old shows or mindlessly scroll TikTok. It’s the disengaged activity you need for a moment until the tide ebbs.

Problems start to arise when taking to Instagram eats up your time. Or maybe you check Slack instead (is that better?) and find three more things to do that seem more manageable, and you leave the original task in the dust. And then you find a task that sets off another wave. So that new task gets left behind. Urgent needs pop up from the last time you did this. You feel like you need to hop on those first. And then you’re in an unending cycle of being late on everything and having to conquer your own brain to get through it.

Or maybe you think you can just switch between conversations and coding and document writing to catch up. Hm.

Multitasking is a myth

Anxiety is an affliction of never knowing the present. The anxious person is always trying to think ahead to predict the future to protect themselves, reliving the (maybe banal, maybe true) horrors of the past to remind themselves that bad feelings are ever-present, while also wondering about simultaneous timelines where you know what other people are thinking, planning, scheming, or are about to pop out from behind a bush. And these thoughts feel parallel, especially in a brain that always feels like it’s churning.

So you would think that an anxious person would be able to multitask better than anyone, and often I fell into that trap: I can write this document while attending this meeting. I can keep this Slack conversation going while I code review. I can have a one-on-one while monitoring an outage (that last one is egregious). I was wrong.

Context switching is a dirty phrase in engineering. It’s the thing that we, especially veterans, cite for why focusing is hard and why day-to-day work gets delayed. “I keep having to answer questions” or “These projects are overlapping and I’m switching between them” or “I’m trying to work while also getting pulled into this conversation.” While multitasking is finally getting its due as just a euphemism for context switching (1 , 2 ), there’s still this perception that people can do it (and are good at it). The old Arrested Development quote: “But it might work for us. ”

So fine. You’ll just put your nose to the grindstone (ick) and knock these things out while requests hang out there. Better to just use the time to get the work done rather than spend time facing up to why the thing is late, right? Well …

You’re not communicating enough

This is the point of no return for many people on the road to burnout. As things start to pile up, the anxious engineer turns inward. We start seeing people not attend meetings, stop returning messages, and leave people twisting in the wind as if they’d vanished. Pummeled by incomplete tasks and assumptions that other engineers are doing their work just fine, there is the potential for catching imposter syndrome. This inward shift creates a vicious cycle of feeling like you’re not good enough and then not doing enough.

I say “catching” imposter syndrome because, to me, imposter syndrome is not a death sentence. It can be terminal for a job if left untreated, but it’s not the end of a career. That is because imposter syndrome is the confluence of several factors – already present insecurity, the toxicity of the work environment, being set up for success, etc.– and not just some latent, forever-chant of “I can’t do it.” People want to feel like they can do things.

I bring up imposter syndrome here because, for the anxious engineer, this can lead to the vanishing of that engineer. If you have someone who keeps asking about a project or a task and you don’t have an answer (or maybe you don’t have the answer they want), you might just stop talking. You’ll stop updating. You’ll make yourself unavailable. Why? Because saying you don’t have what someone wants is scary, and it’s easy to close Slack or just leave the message unread. “I’ll finish this and tell them that I missed the message.” It is a net bad for engineers to leave someone on-read/unread4.

A bad update is better than no update, and asking for help is better than struggling in silence. Someone might get mad about it, but at least everything is out in the open, and people are being transparent. It will feel really bad at first to open up about not having the thing someone is asking for. But that means that people can help make roads for things getting done properly.

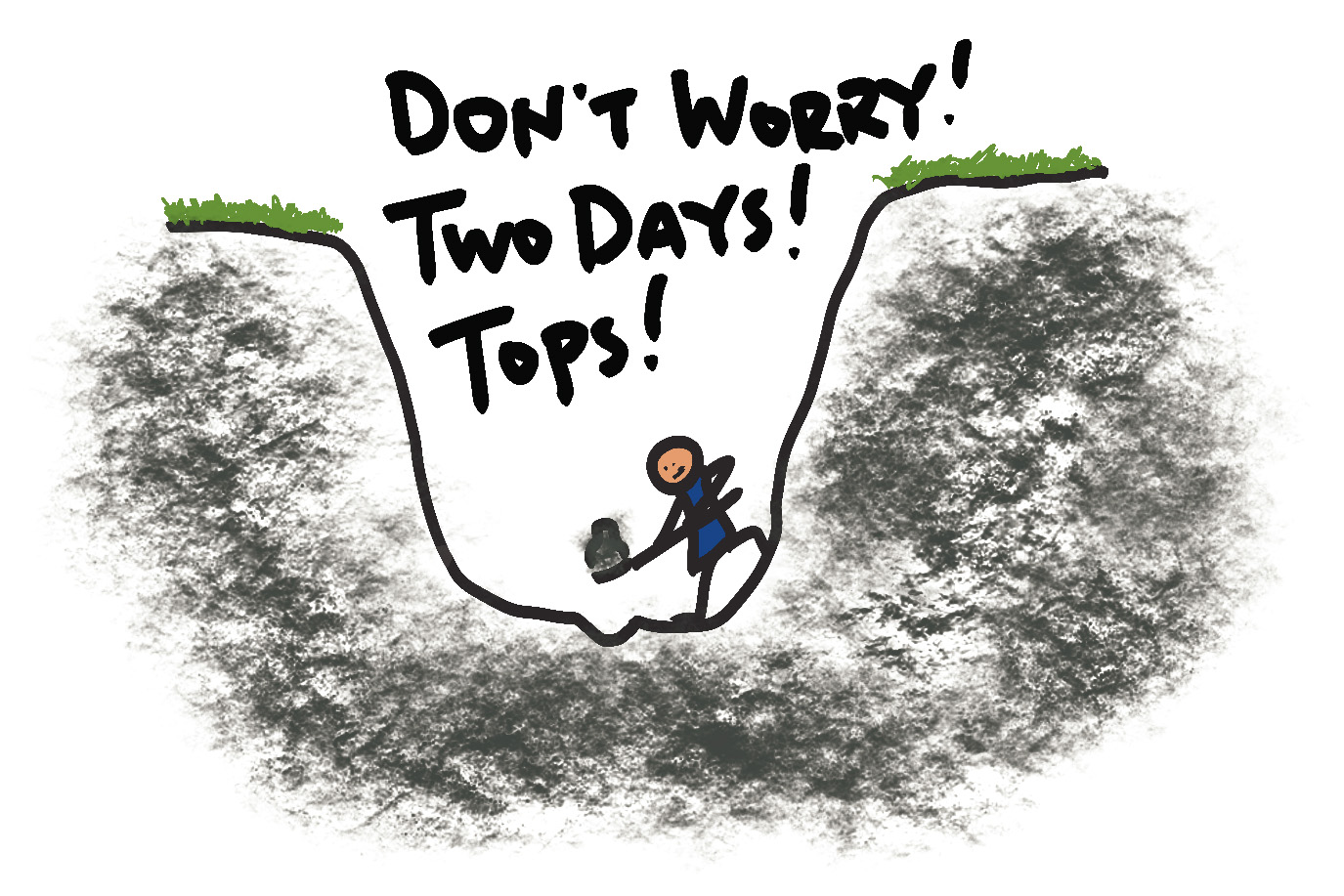

Okay, okay. You’re starting to see the light. Break the bad news that you’re swamped but that you’re working on it. They’ll understand. You’ll just give a timeline that will make it sting less. This week’s worth of work? You’ll have it done by tomorrow afternoon. Maybe you’ll stay up all night to get it done and sleep from 5AM until 7AM. Oh, man. I hate to break it to you, but …

You’re not taking good care of yourself

No one should be cramming. Working more hours than you get paid for is not a badge of honor. Sleeping three hours every night is unsustainable. Sacrificing yourself physically and mentally for a job is doing yourself, your friends, and your family, and, honestly, your team a disservice. If the pit you dig for yourself starts with lacking communication, this is the thing that deepens it.

Your job may ask you to make certain sacrifices, and you can determine whether those sacrifices are normal or not. But when it comes to being buried under work and using your non-work hours to catch up, even your sleep hours sometimes, even when not asked, you are making your life miserable. Why are you doing that?

A recent example of this for me was writing a bunch of documents under a self-imposed and impossible timeline. That “work until 5AM, sleep until 7AM” scenario seemed very specific, didn’t it? I felt like there was a lot of pressure on me to get these documents done, a lot of people needed them, even though I was sick (so I needed more rest, not less), and it was during the early 2025 wildfires5 in Los Angeles (so a bit of a burdensome crisis in our area).

Everyone else had completed or mostly completed their documents in my peer group, and I was still way behind. Instead of admitting that I needed more time, that things were not going as planned, and that there were some factors at play, I blurted out a timeline that didn’t make sense, though if you were to ask me at the time, it made all the sense in the world. “Of course I will be able to turn around essentially eight 7-paragraph essays in two work days along with no interruption to my day-to-day work.” It’s not only unreasonable, it’s self-destructive.

And if I can’t do it in two days that would mean that I can’t do it and that’s impossible because I’m not an imposter, right? RIGHT?

Also, I didn’t even finish it. Instead, I had a breakdown at 4AM, finished as many as I could, and left three more for myself after an early-morning nap.

Burnout requires you to be off-kilter. It feeds on insecurity. It feeds on exhaustion. It feeds on the vicious cycles of bad work habits. Anything that makes you shift your center of gravity so it’s easier for you to topple into the big hole you dug. Maybe managing your workload is hard. Maybe communication is tough. But you can at least sleep a refreshing number of hours. Balance your non-work life with your work obligations. Give yourself a break. Whatever you need to regain your balance.

Ah, all right. So you’ve communicated that you need more time. You’re getting the rest you need. Things are looking more stable. It will still take you a long time to finish all this stuff, but at least you don’t feel like the hole is getting deeper. Just one more thing …

You’re being a jerk by not delegating

The perfect storm of all these things, along with the deepness of your rut, are built on an important assumption: that you have to do all this yourself. No one with imposter syndrome has ever said, “I’m a fraud because I’m not spreading out my workload.” This anxiety makes it hard to see beyond yourself and what you’re supposed to be doing and achieving.

Delegation sometimes has a bad reputation as something managers or higher-level employees do so they don’t have to do any work. But delegation is also how people grow. How do you learn how to do things at the next level without someone trusting you to do that work? Instead of hoarding all the activities to yourself, think about how that could help someone around you grow. Delegation isn’t just about asking for help but also about giving opportunities. You know how to do your job. There are other people you work with who might want to do a job like yours but don’t have the functional knowledge to do it. How else will they be able to grow if you don’t let them have access to the activities that prove they can do the job?

Sometimes the anxious engineer overthinks this. An example: My team was coming out of a nightmare where the project was a mess, timelines were constantly being overrun, and the scope kept changing above my pay grade – your basic night terror of a toxic situation. At the time, I told my team to ignore everything else. If people asked them questions or tried to go around our process, I asked my team to redirect them to me and our product manager. It was an effort to remove the distractions and allow them to just work rather than deal with the disaster. The project was finally released. It did … fine. Then, a year and a half later in talking with a friend after a particularly rough review period, it dawned on me that I’d never given the responsibilities back. Instead, I’d collected more.

Engineers were unclear about how to release a feature. They were unclear about what other teams did and who to talk to. They were unclear about how their own app worked. Why? I wrote the launch docs and published A/B tests. I started the conversations with other teams about our dependencies. I sat in all the meetings, architecture councils, and discovery. People were asking me all the questions, and I was the one giving them answers, so they just sent their questions to me. My team’s foundational knowledge withered in the smoldering ash of my burnout.

He does. As an audience.

Some of that was my job. But there wasn’t a requirement that I was the only one that had to do it. The biggest trick I pulled on myself was that I took all these tasks, and no one told me that no one else was doing all that work. So I just started to assume that I had to do it, and then I burned myself out and hurt my team; the stuff still didn’t get done.

Asking for help is such a powerful skill. If you can make that easy for yourself, that will make so much of this less difficult in the long run. Also, delegation isn’t just about asking for help. It’s also about giving people opportunities. It’s about investing your trust in another person that they can do the job. Team morale can be improved if everyone shares the burden, rather than just shoving the burden on everyone else. And this isn’t just for engineering managers and staff+ engineers. This is for senior engineers to give a larger task to a junior engineer and help them tackle it. It’s pair programming or ensemble programming. It’s getting everyone involved.

So now you know. You can ask for help! You can delegate! You are not alone! The rut should be shallow now! The caveat …

If your workplace is so toxic that you can’t look dumb once in a while, is that a workplace for you?

One of the biggest concerns about the anxious or burned-out engineer is that, as you feel like other people are working without trouble, delivering, coasting, and not bothered by the workload, you must be a fraud. And if you’re a fraud, then asking questions will just show the world that you’re an ignorant lump who contributes nothing. But imposter syndrome does not happen in a vacuum.

If your workplace is not encouraging of questions or accepting of temporary ignorance, if it negatively comes up in reviews that you dared ask about a thing you “should have known,” if being wrong comes with snide remarks, you are in the wrong place. Maybe I shouldn’t say that. You might be the kind of person who likes to work in a place where people “push” each other through pedantry and tactlessness. Maybe you like the challenge of a group of people publicly and mercilessly eviscerating your takes and code so that you can learn. Maybe you believe in the oft-debunked alpha dog theory of things and like having every petty tool at your disposal to get your chance to be that engineer at the top of Code Mountain. I don’t know. Lots of people like to work at places that suck6.

At the end of the day, you have to ask yourself if your burnout is brought on by anxiety or if your workplace stoked it. Will you always struggle with this thing? Will you always need to protect yourself from where you work? That’s a decision for you to make. A former CTO of mine used to say a phrase that sounds gross to me but is descriptive and relevant: Is the juice worth the squeeze? Do you see nothing but ruts in your future even if you develop better engineering habits?

I switched from engineer to manager because I love mentoring and tracking people’s progress on the team. I love being involved in what features are important for us to work on. I love creating processes that make the engineers’ lives easier while also getting features out on time. My previous “in the trenches” managers didn’t do the things for me that I relish doing for my teams. And being the change I want to see in the world (at least my world) inspires me.

Your anxiety may not look like this. But everyone is susceptible to it. I make a living at seeing this kind of thing in other people to help mitigate it, and I couldn’t see it in myself. Hopefully, some of this will help you before you dig yourself in a hole so deep you can’t see out of it, praying for just a little more time.

That last part is how my four-year-old daughter described what my job was: “Meeting, meeting, meeting” and then she’d scream. Pretty accurate, honestly. ↩︎

I threw Microsoft in there, too, with Meta for a nice, roll-off-the-tongue “ma-mang” or a hungry “mmmmmm-ang”. ↩︎

Or at all. 2025 Meta products are a bad scene, man, on every level. ↩︎

For those of you who are reading this and realize that you may have been a victim of my anxiety since I left you hanging and, three days later, said, “Hoo, I missed this message. Sorry about that.”: I also get a lot of Slack messages and sometimes I honestly do miss them. So I don’t mean you, obviously. ↩︎

Hedging my bets by calling them “early-2025” wildfires. Hopefully, we don’t have to worry about national-news-coverage-level wildfires for the rest of the year at least? We pray? ↩︎

I haven’t experienced a workplace like this in a long time, but a burned-out engineer can feel like every workplace is like this. Remote workers get the worst of this since their lives revolve around contextless syntax all day, with no way to get that context easily. This is not a fight for more hybrid and on-site; this is a vote for more places being digital-first. ↩︎